Dr. Paul Winston

Physiatrist, Researcher, Ballet Dancer, Human

The Palace of Versailles—not something you’d expect to play a large role in the life and career of a Canadian physiatrist and medical researcher like myself; but the romantic in me is proud to say that it has. It’s been a common thread throughout some of the most significant moments in my journey.

Versailles’ first appearance was in a voicemail I received just as I began my first year of university:

“Hi there, we’re calling from the Opera Atelier. We’re here performing at the Palace of Versailles in Marie Antoinette’s Theatre as a part of our European tour right now; but we’re heading back to Toronto and we want you to come work with us.” Dance has always been a passion of mine—I performed with the National Ballet for six years out of high school before pursuing university with the goal of medicine—so the opportunity to continue dance with such a renowned opera company was an honour, and a great way for me to pay for my undergraduate science degree.

Today, as a physiatrist at Victoria General Hospital, I think back on this time often. Sometimes you can find me dancing in the empty halls and clinic rooms of the hospital. Here is a clip with Dr. Eve Boissonnault my former fellow from Montreal.

“The opportunity to continue dance with such a renowned opera company was an honour, and a great way for me to pay for my undergraduate science degree.”

“I didn’t even consider myself a researcher at the time. However, as I write this, our paper has been cited over 225 times”

Funnily enough, dancing not only helped fund my education and medical school track, but also played a part in leading me to research.

As a ballet dancer, I developed a hip problem–a very painful clunk in my movement. None of the sports doctors, surgeons or physiotherapists in Toronto were able to diagnose what was causing my problem, let alone treat it. My hip problem is one that I share with many other dancers and athletes, so years after my dance career, during my residency, I created a residency research project on the subject in partnership with a radiologist. Using ultrasound equipment, he was able to identify the problem: a snapping hip tendon known as the iliopsoas. No one else was using ultrasound like that in 2005.

At the time, I thought our work was relatively obscure. I didn’t think anyone would care. Academia was not my interest, and I didn’t even consider myself a researcher at the time. However, as I write this, our paper has been cited over 225 times and is considered a seminal work on the subject. I have always kept this in the back of my mind. It showed me that I could have an impact by seeking solutions to problems that had no answer.

After finishing my residency in Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation in Toronto, I moved to Victoria. Since coming here, I have worked very closely with two colleagues, interventional radiologist Dr. Daniel Vincent, and plastic surgeon Dr. Emily Krauss. We have collaborated for many years to help treat spasticity: a painful, disabling neurological condition commonly caused by strokes and brain injuries.

In 2017, we had the opportunity to attend a conference that would be very influential for us, serendipitously hosted at the Palace of Versailles. We met with doctors in our field from around the world to share ideas. I was blown away by the treatments offered by our French and Italian counterparts. They were so far beyond anything we could provide, or anything that I thought was possible.

While at that meeting I said to my colleagues, “We’re going to create a leading program in North America”. It was a bit of a joke because we didn’t have the money or the team at the time. You see, funding is an ongoing challenge for clinical-based research like ours. We don’t have the same backing as academic research institutes.

But we made it happen through grants and funding. I am grateful to Victoria Hospitals Foundation donors who support our research work through Island Health Research and the Health Authority. It is incredibly difficult to maintain, but the beautiful thing about clinical research is how quickly we are able to innovate. Given the number of patients we see daily, I am constantly learning and evolving my care to provide the best results I can for my patients. It only makes sense to translate this into research that can be shared and developed more broadly.

After the 2017 meeting in Versailles, we spent the next two years developing a brand-new non-surgical way to treat spasticity. Our technique combined my skills in ultrasound, Dr. Krauss’ surgical knowledge of nerves, and Dr. Vincent’s bold new idea to utilize cryoneurolysis: a very rare form of pain treatment through nerve freezing. And it started working.

We returned to Versailles in 2019 with this new treatment, which we called cryoneurolysis for spasticity, and shocked our European counterparts the same way they had shocked us two years previous. The results we were seeing with cryoneurolysis were beyond even what surgical options could provide. In Marie Antoinette’s Palace, 100 years after the Treaty of Versailles was penned, we were told we were now positioned to set up the next 100 years of spasticity innovation.

Since then, I have devoted myself to developing this treatment further, finding funding for our work, and improving the care I can offer my patients every day. It has been far from easy, but seeing the transformation it has provided is worth it. Brain injury patients able to brush their own hair for the first time in years. Stroke survivors able to button up their coats without assistance. A married couple holding hands again. Children with cerebral palsy running, throwing a ball, hugging their parents.

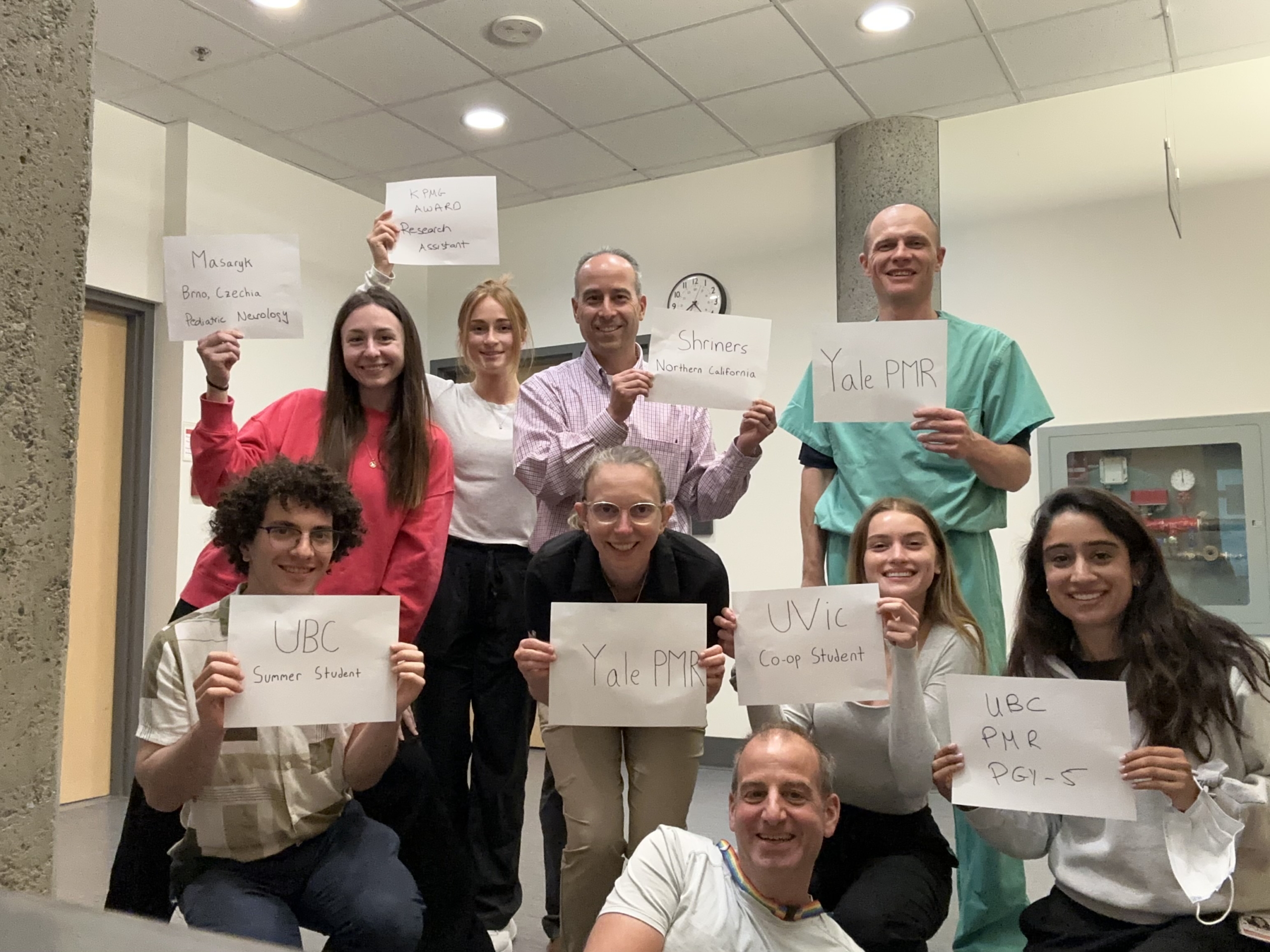

By constantly seeking out research and donor funding, our rehabilitation clinic at Victoria General Hospital is now filled with bright young co-op students and research assistants who can help doctors give patients the interdisciplinary care they deserve.

The work we do here in Victoria is now being replicated at Harvard, Oxford, Mount Sinai, New York, Houston, and many other sites across the United States, Canada and Europe. Every month, doctors from South America, the Middle East, and all around the world come to train in our clinic. We have created our own Versailles, a hub for global impact. You can watch a documentary about our whole story here.

When I was a ballet dancer with a hip problem, I was told, “There’s nothing more we can do for you”. Now, as a clinical researcher, I see people in the same position every day; but I get to ask, “What if there is?”

“We have created our own Versailles, a hub for global impact.”

They are humans first, who put other humans first.

More than 8,900 caregivers and staff work around the clock in our Victoria Hospitals

#HumansFirst is dedicated to sharing the stories from behind our hospitals’ frontlines. These stories remind us that those who provide care and keep the lights on in our hospitals also have lives outside of them. They have family and friends, they enjoy hobbies and interests, and they have all lived through their own personal triumphs and heartbreaks. Like all of us, they are human, and they have a story to tell.

Hear from one of Dr. Winston’s patients

Local spasticity patient, Sarah Millard, shares about the impact that Dr. Winston’s research has had on her life.